Love of Language

By Jayne Blanchard

Director John Vreeke has a genius for taking dense, accreted material

and

spinning it into something unexpectedly magical and immediate. Last

summer,

he did it with the Washington Shakespeare Company's transcendent

production

of "Lady Chatterley's Lover," a novel remembered by everyone for the

scorchy

parts, although it's really D.H. Lawrence's hothouse diatribe on

stifling

class distinctions in 20th-century England.

At Baltimore's Everyman Theatre, he took the

exposition-laden comedy "Red Herring" and made it into a slap-happy,

commie-hunting 1950s farce

that was as snappy as a Mickey Spillane potboiler.

Now Mr. Vreeke has done it again, this

time for Woolly

Mammoth and Theatre J, with a wrenchingly affecting and beautifully

acted

production of Tony Kushner's "Homebody/Kabul." As theater mavens

already

know, Mr. Kushner never met a monologue he didn't like, as evidenced by

the

eight-hour masterpiece "Angels in America," which gave the phrase

"Faulkner-esque"

a whole new meaning. Now Mr. Vreeke has done it again, this

time for Woolly

Mammoth and Theatre J, with a wrenchingly affecting and beautifully

acted

production of Tony Kushner's "Homebody/Kabul." As theater mavens

already

know, Mr. Kushner never met a monologue he didn't like, as evidenced by

the

eight-hour masterpiece "Angels in America," which gave the phrase

"Faulkner-esque"

a whole new meaning.

His love of language is evident and infectious, and

the

nearly four-hour "Homebody/Kabul" introduces us to such obscure morsels

as

"antilegomenoi" (volumes of cast-off or forgotten knowledge) and

"periplum"

(a word coined by Ezra Pound to describe a tour that takes you round,

then

back again), among others.

Mr. Kushner also imparts a historian's delight in

world

history. Even if you believe your college lecture days are long behind

you,

you have to admire the playwright's audacity for starting "Homebody"

with

a one-person sirocco of a speech that whips you through thousands of

years

of Afghanistan's upheavals in little more than an hour.

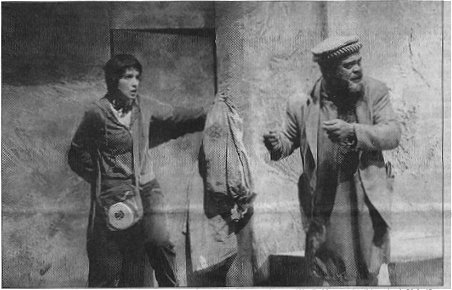

The play begins in 1998 with the Homebody (a

charmingly distracted and gracious Brigid Cleary), an eccentric and

bookwormy Englishwoman, sitting in a chair surrounded by a crescent of

recently purchased Afghan hats.

The story of these hats, bought for a party, leads the Homebody through

a

richly convoluted monologue that touches on the Taliban, Islam,

anti-depressant use, unhappy modern marriages, reading and the wide

gulf between the words "maybe" and "do."

An old travel guide leads her to an impetuous trip

to

present-day Kabul, an act that sets the play in motion.

Her husband, Milton Ceiling (Rick Foucheaux), a

nervous

computer scientist, and daughter Priscilla (Maia DeSanti) travel to

Kabul

to find out what happened to her. Did she die an excruciating death at

the

hands of the Taliban, as reported, or did something more romantic and

strange

occur? The answer to the Homebody's fate is never quite settled, as the

various

characters in Kabul manipulate and exploit Milton and the prickly and

belligerent

Priscilla. (Seeing Miss DeSanti fighting with her burqa is alone worth

the

price of admission.)

The gorgeous torrent of language and the

in-love-with-words penchant Mr. Kushner displays aside, the most potent

aspect of "Homebody/Kabul" is its characters.

They are a striking assemblage, ranging

from a former librarian

(Jennifer Mendenhall) nearly driven mad by the Taliban's restrictions

on

women; to a fetchingly dissolute British consul named Quango Twistleton

(Michael

Russotto), named after a character in a P.G. Wodehouse novel; to a

guide

(Doug Brown) who may or may not be smuggling terrorist secrets on

documents

he says are poems written in Esperanto; and a former Afghan actor

(Aubrey

Decker) who speaks in snippets of Sinatra songs and other forbidden

pop-culture

references. They are a striking assemblage, ranging

from a former librarian

(Jennifer Mendenhall) nearly driven mad by the Taliban's restrictions

on

women; to a fetchingly dissolute British consul named Quango Twistleton

(Michael

Russotto), named after a character in a P.G. Wodehouse novel; to a

guide

(Doug Brown) who may or may not be smuggling terrorist secrets on

documents

he says are poems written in Esperanto; and a former Afghan actor

(Aubrey

Decker) who speaks in snippets of Sinatra songs and other forbidden

pop-culture

references.

Mr. Vreeke skillfully handles this panorama of human

behavior,

enabling the actors to create vivid, brief sketches without resorting

to

stereotype. He saves the big guns for the main characters, though,

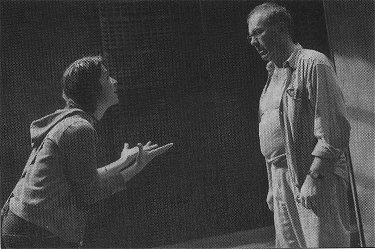

starting with Mr. Foucheaux as Milton. Every scene in which Mr.

Foucheaux appears —

including a hung-over showdown with his volatile and fragile daughter

and

one in which Quango silkily introduces him to heroin — crackles with

honesty

and a terrible beauty.

No one does mute vulnerability like Mr. Foucheaux,

and

he is ably matched by Miss DeSanti as the strident Priscilla. Where Mr.

Foucheaux

is all quiet composure and observation, Miss DeSanti is angry response

and

physical rejection.

Mr. Russotto also has some disquietingly sensual

moments

playing the lonely, erudite junkie, as does Mr. Decker as the

culture-hungry former actor. Miss Mendenhall's strident portrayal of

the librarian jars at

first, before settling down into a searing performance.

***1/2

© 2004 News World

Communications,

Inc

Hide and Seek

Tony Kushner’s ''Homebody / Kabul'' at Wooly Mammoth

by Jolene Munch

Published on 03/11/2004

Before August 1998, before President Clinton ordered the

United

States to retaliate against a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan by bombing

the

city of Kabul, and before the words Al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden became

reluctant

fixtures of the collective American conscious, an annoyingly literate

British

housewife sits in solitude, reviewing passages from an outdated travel

guide

on the remote, exotic landscapes of Afghanistan. She is Mrs. Ceiling,

"The

Homebody " in Tony Kushner’s Homebody/Kabul, and she is ready

for

exquisite adventure.

The estranged Ceiling family -- father Milton and daughter

Priscilla

-- dash off to Kabul in search of their missing wife and mother. Here

in

this devastating, mysterious country, far from the comforts of their

London

home, they are first told that Mrs. Ceiling died in a minefield while

searching

for the Grave of Cain, Adam’s first son. But soon thereafter, Priscilla

discovers that the truth may be far more difficult to bear.

|

There are rumors that The Homebody has abandoned her former

identity

and converted to the Islamic faith, marrying a Muslim in Kabul and

forging

a new persona. It is impossible news to imagine, that a citizen of the

free

world would betray her own culture, her carefree way of life, to assume

the

burdens of a oppressed woman in Afghan society. Is it possible that a

self-indulgent

Westerner could willingly sacrifice their freedoms, their very

identity,

to become someone else, to embrace and assimilate to a culture and

religion

so far removed from their own? It’s a difficult question to ask, but

one

that is perhaps even more awkward to answer.

|

Tony Kushner, best known for Angels in America, has

never

been afraid to tackle some of the most controversial and convoluted

issues

of our time. Kushner started writing Homebody/Kabul in 1999,

before

American history became forever altered on September 11, 2001. The play

has

since undergone significant rewrites since its December, 2001 New York

premiere.

Kushner’s latest version is a dreadfully long marathon, the length of

which

would be forgiven if the playwright were able to keep his audience

engaged

and interested. Instead, his long-winded lyrical speeches and

never-ending

scenes make for a grating theatrical experience. It’s an important,

enlightening

story, but it does not entertain and rarely enthralls. In fact, it is

just

plain difficult to digest.

|

Perhaps the evening begins on the wrong foot. For a large

portion

of the first hour, The Homebody (Brigid Cleary) does not move from her

garden

chair, reciting an endless monologue as a lonely intellectual who finds

old

travel guides "irrelevant and irresistible. " Her curiosity for foreign

lands

and passion for ancient history should be endearing, not irritating,

and

her frequent asides leave room for us to empathize with her familiar

boredom.

Although Kushner’s material sounds amusing, Cleary’s stock delivery

with

its muffled dialect fails to delight.

|

Once we arrive in Kabul in the second act, the play gains

momentum,

shaping a much different, darker story. Director John Vreeke

successfully

conveys a shadowy, volatile society filled with civil conflict and

political

intrigue, in part attributed to the inspired lighting design from Colin

K.

Bills. Kushner’s characters speak in native Pashto and Dari languages,

which

sharply contrast the varying degrees of Cockney demonstrated by the

Ceiling

family. These subtle nuances are brought to life through Vreeke’s

precise details, including uncomfortable, violent moments that are

rarely believable

in a staged environment.

Aside from Cleary’s lukewarm title character, the actors are

uniformly

solid, with exceptional supporting performances from Doug Brown,

Michael

Russotto, and Jennifer Mendenhall, emotionally wrenching as a desperate

librarian

who can barely remember the alphabet. Reciting a fluent mix of several

languages,

Mendenhall is the real revelation in an evening of burqa-clad

anonymity.

Homebody/Kabul

Written by Tony Kushner

Presented by Woolly Mammoth & Theatre J

At the DCJCC

1529 16th St. NW

|

|

Like two polar cables trying to connect to the same dead

battery,

Rick Foucheux and Maia DeSanti offer affecting portrayals as a father

and daughter helplessly trying to remain intact while everything around

them

falls apart. Foucheux is especially adept at mixing a peculiar cocktail

of

apathy and horror for his bumbling Milton.

Sometimes it takes a personal, self-examining journey to

understand

what a particular piece of theatre is really about. After

Kushner’s

nearly four hour-long Homebody/Kabul, the audience is

ultimately left

to decide for themselves whether they have just witnessed an

exposé

under the guise of commentary on East-West politics and culture, or if

the

"spectacle of suffering " presented lends meaning and depth to the

argument that it is possible to become so disenchanted with

familiarity, freedoms

and all, that one can be willing to shed their skin for life in a

vastly

different world.

THEATER

THEATER

Homebody/Kabul For an

hour,

Brigid Cleary's mousy housewife commands the stage with nothing but a

certain

dotty charm and a carry-bag full of woven Afghan hats. Those, and the

delirious

monologue Tony Kushner has given her--a looping, free-associative

account

of a London shopping expedition that takes in 3,000 years of history,

meditations

on the function of antidepressants and the nature of magic, and a bit

of

Sinatra, too. By the end of her time onstage, we love her, a little

wistfully,

perhaps, but unreservedly. And then she disappears: Seduced by the

romance

of a 33-year-old travel guide she's been reading to us and by the

horrors

she's been reading in the newspapers, she decamps to Kabul, just as

President

Clinton bombs suspected terrorist camps in Afghanistan. Kushner's

genius

has always been in the way he conflates vast concerns with the lives

and

tics and foibles of his characters, and here his Homebody's

obsession--with

"a pickpenny library of remaindered antilegomenoi"--points up the

argument

he'll make later, when her family has gone looking for her only to

discover

how alien and angry a city can seem. It's not that the world's people

don't

know each other, the sweep and wail and wonder of Homebody/Kabul

suggest;

it's that we forget each other. It's that we don't try hard enough to

hold

on to what we've learned; we don't look past our parochial concerns to

the

bigger picture. Cleary, whose performance is a marvel of dead-on craft

and

off-kilter appeal, is the evening's unquestioned triumph, but the rest

of

John Vreeke's cast does pretty formidable work, too, and the Theater

J/Woolly

Mammoth co-production is a thing of dark and lapidary beauty. (TG)

District

of Columbia Jewish Community Center Goldman Theater, 1529 16th St. NW.

Thursdays

& Wednesdays at 7:30 p.m.; Saturdays at 8 p.m.; Sundays at 7 p.m.;

matinees

Sundays at 2 p.m. $30-$39 to April 11 (800) 494-8497

Homebody/Kabul For an

hour,

Brigid Cleary's mousy housewife commands the stage with nothing but a

certain

dotty charm and a carry-bag full of woven Afghan hats. Those, and the

delirious

monologue Tony Kushner has given her--a looping, free-associative

account

of a London shopping expedition that takes in 3,000 years of history,

meditations

on the function of antidepressants and the nature of magic, and a bit

of

Sinatra, too. By the end of her time onstage, we love her, a little

wistfully,

perhaps, but unreservedly. And then she disappears: Seduced by the

romance

of a 33-year-old travel guide she's been reading to us and by the

horrors

she's been reading in the newspapers, she decamps to Kabul, just as

President

Clinton bombs suspected terrorist camps in Afghanistan. Kushner's

genius

has always been in the way he conflates vast concerns with the lives

and

tics and foibles of his characters, and here his Homebody's

obsession--with

"a pickpenny library of remaindered antilegomenoi"--points up the

argument

he'll make later, when her family has gone looking for her only to

discover

how alien and angry a city can seem. It's not that the world's people

don't

know each other, the sweep and wail and wonder of Homebody/Kabul

suggest;

it's that we forget each other. It's that we don't try hard enough to

hold

on to what we've learned; we don't look past our parochial concerns to

the

bigger picture. Cleary, whose performance is a marvel of dead-on craft

and

off-kilter appeal, is the evening's unquestioned triumph, but the rest

of

John Vreeke's cast does pretty formidable work, too, and the Theater

J/Woolly

Mammoth co-production is a thing of dark and lapidary beauty. (TG)

District

of Columbia Jewish Community Center Goldman Theater, 1529 16th St. NW.

Thursdays

& Wednesdays at 7:30 p.m.; Saturdays at 8 p.m.; Sundays at 7 p.m.;

matinees

Sundays at 2 p.m. $30-$39 to April 11 (800) 494-8497

Copyright

© 2004 Washington Free Weekly Inc.

Tony Kushner's latest

play

Homebody/Kabul at Theater J

When Woolly Mammoth and Written by Tony Kushner. and Theater J

announced

that this season would see a collaboration on Tony Kushner's latest

play,

theater lovers throughout the Potomac Region took notice. Expectations

were

high, for here was a play by the man who wrote the emotionally smashing

Angels

in America, which all reports indicated was a perfect match for Theater

J's

sensitivity to the moral issues raised in that war torn quadrant of the

earth

and Woolly Mammoth's proclivity to treat the unusual with energetic

flair.

No one need fear disappointment - the results on stage meet the high

expectations.

The show is as rich and varied as had been hoped. It may not supplant

Angels

in America as Kushner's masterpiece, but it provides a night of

fascinating,

absorbing and memorable theater.

Storyline: An English lady, unhappy in her

marriage and not too thrilled

with her relationship with their daughter either, becomes fascinated

with

an out of date tourist guide to the Afghan capitol of Kabul. Suddenly,

she's off to the mysterious middle-east where she disappears into the

Taliban-controlled

closed culture of that poverty ridden but proud country just as the

Americans

bomb a suspected terrorist camp in Kkhost. Her husband and daughter

travel

to Kabul to find her. The husband believes initial reports that she had

been

killed but her daughter travels deep into the back streets of the city

in

search of the truth. Storyline: An English lady, unhappy in her

marriage and not too thrilled

with her relationship with their daughter either, becomes fascinated

with

an out of date tourist guide to the Afghan capitol of Kabul. Suddenly,

she's off to the mysterious middle-east where she disappears into the

Taliban-controlled

closed culture of that poverty ridden but proud country just as the

Americans

bomb a suspected terrorist camp in Kkhost. Her husband and daughter

travel

to Kabul to find her. The husband believes initial reports that she had

been

killed but her daughter travels deep into the back streets of the city

in

search of the truth.

The key item in the title is the slash, for there really are two plays

here

joined at the heart. The first hour is a solo performance piece,

fascinating

on its own merits but immeasurably enriched by what follows, and what

follows

is significantly enhanced by what precedes it. One of Kushner's

incredibly

personal personalities, the English lady known as Homebody, is brought

to

vibrant life by Brigid Cleary. She's all alone on the stage but not all

alone

in the room for she draws the entire audience into communication with

her. Cleary reacts to the audience's reactions to her statements,

turning a monologue

into a conversation. (It helps that the house lights which are faded to

black

when the stage is darkened to start the show are brought back up to

about

a third so the audience isn't in the dark and it appears that Cleary

can,

in fact, see them.) Her presentation of the portions of the guide book

that

so fascinate her character is peppered with self-revealing asides,

salted

with the kinds of additional information that a woman who loves to read

would

have stored in her brain and sweetened with an enthusiasm for life that

makes

you awfully glad you met her.

The Kabul part of Homebody/Kabul - the part that is populated with a

host

of intriguing characters - is not quite as uniformly satisfying as that

first

segment, but it is never less than fascinating and occasionally

spellbinding.

The spellbinding part comes late in the evening when Jennifer

Mendenhall

makes her appearance as an Afghan woman wanting to leave the country

because

her husband wants to take a new wife. Her tantrums are enough to make

you

believe her husband would want to be rid of her under any circumstance,

but watch closely for they are so skillfully modulated that they

ingratiate rather

than repel the listener. This is a trick that Maia DeSanti as

Homebody's

daughter hasn't quite mastered. Her whining outbursts, as well

motivated

as they are, become tiresome and seem petulant when her character

certainly

has a great deal to whine about. In between the two extremes are a

number

of fascinating individual portraits including Doug Brown as an

inscrutable

guide/poet, Aubrey Deeker as an Afghan who loves the lyrics of Sinatra

songs,

Conrad Feininger as an infuriatingly logical Mullah and, most notably,

Rich

Foucheaux as the husband who may not have cared a lot for Homebody in

the

waning era of their marriage but whose fate all but destroys him.

The world which Homebody's family searches is confined in but

strikingly

staged on Lewis Folden's earthen toned set given depth, suspense and

dramatic emphasis through Colin K. Bills' effective lighting design and

Dave McKeever's

haunting soundscape of the backstreets of Taliban-held Kabul. The fine

thing

about the visual and aural design is it remains a background for the

actors

as they create the characters out of Kushner's words, but it seems to

amplify

them - not in volume and not in any audio augmentation sense, but in

the

way they frame the moments, add depth to the spaces between

characterizations

and provide the audience with a sense of the feel of backstreet Kabul.

It's

quite a trip.

'Homebody/Kabul': Land of Lost Chances

By Peter Marks

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, March 10, 2004; Page C01

In "Homebody/Kabul," playwright Tony Kushner gives himself a

tough

act to follow. For the first hour of this absorbing exploration of

broken

hearts and shattered nations, we're in the thrall of the Homebody, a

hilariously literate Englishwoman with a desperate urge to flee the

suffocating normalcy of life in London.

Through her restless imagination, she has already begun her

escape, and as she reads on and on to us from a frayed guidebook to the

Afghan capital,

her relish for the exotic, faraway city becomes infectious. She makes

it

sound mysterious and alluring, another Casablanca. In Brigid Cleary's

smashing

performance, the Homebody is irresistible, too, vivacious and wounded

and

balmy and comic, a character so vivid that you're not inclined to

encourage

her to yield the stage.

The marvelous hour in Cleary's company is a whole play unto

itself. That 21/2 additional hours of exposition are to follow is the

tricky assignment Kushner must navigate in "Homebody/Kabul," the 2001

play receiving its Washington

premiere from Theater J and Woolly Mammoth. To the extent that the

Homebody's

aura lingers long after she has vanished, the work retains an emotional

force.

The panic at her disappearance in Taliban-controlled Kabul, where her

husband,

Milton (Rick Foucheux), and daughter Priscilla (Maia DeSanti) go in

search

of her, feels authentic.

But it's also the case that "Homebody/Kabul" grows murkier and

less interesting the further it strays from an accounting of her fate.

(The play,

it should be added, is never uninteresting.) It's only in the emergence

later

on of an Afghan character, a tormented wearer of the burka (the gifted

Jennifer

Mendenhall) who has her own urgent need for escape, that the play

regains

its powerful hold. The other pivotal theme, the troubled Priscilla's

quest

for peace with her mother and with herself, is as shrill and

overindulged as the mystery of the Homebody is fascinating.

At the time of its opening three years ago at the New York

Theatre

Workshop, "Homebody/Kabul" was Kushner's most ambitious work since the

Pulitzer- and Tony-winning "Angels in America." "Caroline, or Change,"

a musical memoir

of race relations in Louisiana that is moving to Broadway next month,

may

now own that distinction. "Angels" was the playwright's wrath-filled

elegy

to an America in the grip of AIDS. "Homebody/Kabul" is also concerned

with

grief, the despair at the loss of a loved one, of a culture, of

identity, of personal freedom. Like "Angels," too, it's a grab bag, a

story assembled from a passel of perspectives. But fewer of the

perspectives in "Homebody" muster any real intensity. The Afghan

voices, in particular, do not always fulfill the dramatist's mandate

for radiant individuality.

Kushner has tightened the work since its New York debut, and

as

a result of John Vreeke's taut mounting on the compact Goldman Theater

stage

in the DC Jewish Community Center, the production usefully sustains an

air of unease. The casting of some of the Afghan roles is questionable

-- the shifty-eyed Taliban minister of Conrad Feininger, for instance,

comes across as a B-movie sinister guy -- and too many attempts are

made by too many actors

to show off in their freak-out "moments."

Still, an American playwright of Kushner's skill and passion

taking on the geopolitical tragedy of Afghanistan could not make for an

evening of

more consequence. Set in the late 1990s and written before 9/11,

"Homebody" is like a tour of ruins -- in this case, the rubble left by

3,000 years of

steamrolling conquerors and superpowers.

The Kabul extolled in Cleary's guidebook bears little

resemblance

to the armed camp it has become under the Taliban. Lewis Folden's set

of

stone and metal fencing, lighted ominously by Colin K. Bills, conjures

a

colorless combat zone. The only visual relief comes from an unlikely

source,

the splashes of color sported by the Afghan women in burkas; as

designed

by Helen Q. Huang, the costumes are made to seem heavy, ungainly, a

burden.

Much of the plot revolves around Milton and Priscilla's

efforts

to unravel the mystery of the Homebody's disappearance. Foucheux's

Milton

is a finely wrought puddle of a man: sobbing and cowering in his hotel,

he

withdraws into a solipsistic heroin-fed stupor, assisted by Quango

(Michael

Russotto), a British expatriate so debauched he rifles Priscilla's

backpack

for knickers to sniff. It is left to Priscilla to venture out and try

to

find the truth, a quest that leads her to Khwaja (Doug Brown), who may

or

may not simply be the mild-mannered, Esperanto-spouting poet he claims.

Kushner leads us from the lush, cerebral world of the Homebody

to

the scarred, barren landscape of Kabul so that we, too, can feel the

loss

of what Milton and Priscilla had and never appreciated. Priscilla,

however, is such an unpleasant mess -- embittered, hostile, arrogant,

unbending --

that it's difficult to accept her as a touchstone for the play. Though

DeSanti

conveys Priscilla's pique convincingly, in defiant drags on a cigarette

and

little foot-stomping tantrums, she has little more success in opening

Priscilla

up to us than have other actresses in the role.

Much more accessible and rewarding is Mendenhall's Mahala, an

urbane woman who has not borne the years of intellectual deprivation at

all well. Once a librarian -- like the Homebody, she's obsessed with

books -- she has

been driven to the edge of madness by the strictures of misogynistic

religious

rule. Mendenhall finds the vulnerability in Mahala, and the fury; her

anger

is as palpable as Cleary's joie de vivre.

What Vreeke's production makes so admirably clear is the bond

these confined women, gasping for new life, share. It's the most vital

link in the

play, the one that most persuasively justifies the backslash in the

title:

in Mendenhall's Mahala, a Homebody can truly be found in Kabul.

Homebody/Kabul, by Tony Kushner. Directed by John Vreeke.

Sets,

Lewis Folden; lighting, Colin K. Bills; sound, Dave McKeever; costumes,

Helen Q. Huang. With Michael Kramer, Ted Feldman, Aubrey Deeker.

Approximately 3

hours 30 minutes. Through April 11 at Goldman Theater, DC Jewish

Community Center, 1529 16th St. NW.

© 1996- The Washington Post Company

Such a torrent of words to wash over us! Such a polymath

spate

of untranslated Pashtun, Dari, French, and Esperanto, and yet all is

understandable. Such a river of wailing, of keening.

The opening scene of the play, a 58-minute monologue by a

40ish Englishwoman,

the Homebody, is mastered by Brigid Cleary. The Homebody recalls Harper

Pitt:

she follows the pattern of Kushner's pixilated heroines prone to

hallucination.

In a stunning rant within the monologue, she gives voice to an Afghan

merchant

who epitomizes his ruined country:

Look, look at my country, look at my

Kabul,

my city, what is left of my city? The streets are as bare as the

mountains

now... the people who ruined my hand were right to do so, they were

wrong

to do so, my hand is most certainly ruined, you will never

understand...

The Homebody disappears to Afghanistan and the scene shifts

from London to Kabul in 1998, where her family are seeking her. While

her husband

Milton Ceiling (well-played by Rick Foucheux) rarely stirs from his

hotel

room, her daughter Priscilla finds a Tajik guide, Khwaja Aziz

Mondanabosh,

portrayed with sly dignity by Doug Brown. The Ceilings eventually

return

to London with something more than they left with, and something less.

Colin K. Bills mounts lighting instruments on the floor so

that much

of director Vreeke's inventive action can take place lying, sprawling,

kneeling

on the deck.

The play takes us on a trip, but refuses to lay out tidy

lessons

for us. We're left a little adrift, wandering down a ruined street.

In April, 2002, Kushner wrote in an afterword to the play as

published

in book form:

If lines in Homebody/Kabul seem

"eerily prescient"...

we ought to consider that the information required to foresee, long

before

9/11, at least the broad outline of serious trouble ahead was so

abundant

and easy of access that even a playright could avail himself of it...

|