The Tattooed Girl

The Tattooed GirlDirected by John Vreeke

WASHINGTON TIMES

Theater J finds

'Tattooed Girl's' heart![]()

![]()

![]()

Mr. Vreeke has a way with wordy plays, as demonstrated by his gifted turns with Tony Kushner's "Homebody/Kabul" and a spoken-word adaptation of D.H. Lawrence's "Lady Chatterley's Lover." He has his work cut out for him with "The Tattooed Girl," which runs slightly more than two hours but, because of its blustery torrents of professorial discourse, seems much longer.

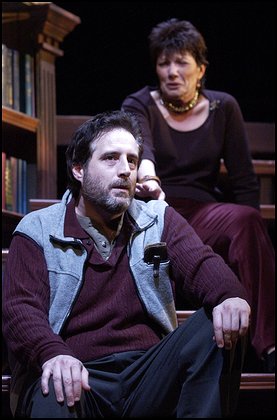

The intellect forming the "mind" of the play is Joshua Seigl (Michael Russotto), the author of a famous novel about the Holocaust written when he was in his 20s. Years later, Joshua has become reclusive and odd, holed up in a big house — rendered by Dan Conway as a book-filled fortress — with only a raging case of writer's block to keep him company.

Recently diagnosed with a degenerative nerve disease, Joshua decides he needs an assistant. A wryly funny sequence details the interview process as a parade of candidates descends on Joshua's study (all played with shape-shifting grace by Karl Miller), each more pretentious or nerdily desperate than the one before.

In a college bookstore, he chances upon Alma Busch (Miss Shupe), who seems straight out of "Deliverance" country. Crude, rural and in thrall to a nasty crystal meth habit, Alma seems an unusual choice for Joshua's rarefied world. Yet he sees something in this strangely tattooed, pebble-brained girl and hires her.

Miss Oates does not tell us much about Alma, hinting that the tattoos scrawled over her neck and arms are the result of a bad drug deal. The halting speech and body curled into itself like a kicked dog's suggest a woman who has been mistreated and discarded pretty much since birth. As the damaged heart of the play, she attracts abusers, in this case a low-life waiter named Dmitri (Christopher Browne), a pimp, drug dealer and rabid racist all rolled into one.

Joshua becomes enchanted by Alma's combination of ignorance and grit, and her presence sparks a creative resurgence as he decides to write the sequel to his great Holocaust novel, a futuristic work in which people have no memory of history, leaving him to ponder, "What are their souls like?" However, Joshua is unaware of Alma's feral, deep-seated anti-Semitism, which has her believing that "Jews caused 9/11" and that the Holocaust never happened.

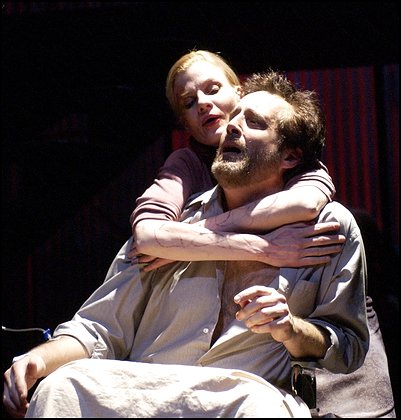

Joshua is the first person in Alma's life who treats her with respect. In his employ, she begins to see her worth. Alma's ascent out of the pit of violence and manipulation is glorious to behold. Miss Shupe gives us a harrowing portrait of a young woman who goes from victim to someone clumsily beginning to stand up for herself.

You wish the rest of the play were as richly satisfying as Miss Shupe's performance. Miss Oates goes for a more hopeful ending than in the novel, but it seems pat and contrived. Though Mr. Russotto deftly captures the ivory-tower imperiousness of a literary giant, his Joshua never reaches the emotional complexities of the character of Alma.

Cam Magee is wasted in the one-note role of Joshua's histrionic sister, Jetimah. Mr. Browne, on the other hand, makes the most of the one-track evil of Dmitri.

"The Tattooed Girl" pontificates about Holocaust deniers, bigotry and ethnic hatred, but that is not what affects you in this play. Instead, you are moved by Alma's journey from dark suspicion to a tentative sense of trust.

Anti-Semitism plays role in Joyce Carol Oats play With powerful performances at Theater J

By Lisa Traiger

A tattoo is a desecration, not a decoration; a work of malice, not art; a defilement of the body rather than an adornment, that is, at least within the confines of traditional Jewish practice.

The tattoo also carries for many, even today, connotations of the Holocaust, of sequential and orderly numbers forcefully embedded into forearms of Jewish men, women and children. The marker, unerasable, became for many the ever-present reminder of the unthinkable.

For prolific novelist, playwright and Princeton University professor Joyce Carol Oates, the tattoo marks her main character Alma as victim, a scarred human, forced always to bear her burden publicly -- tattoos burned into her face, neck and forearms.

But in The Tattooed Girl, on stage at Theater J through Feb. 20, Oates' foil for Alma bears no physical brandings, yet he, too, is marked, his family's past forever implanted, ready to surge forward at the most inopportune of moments.

Oates' newest work is one more coup for the Washington DC Jewish Community Center's resident troupe, which nurtured this world premiere production of The Tattooed Girl under the insightful direction of John Vreeke.

An adaptation of the author's post-9/11 novel of the same name, published in 2003, the work takes a big picture view of America by focusing its lens sharply on two distinct and distinctly differing characters, Alma, a working-class woman who has run short of options, and Joshua Siegl, a faded literary star closing in on 40, who had caused a stir with the publication of his first novel when he was all of 26.

This unlikeliest of pairs soon forges an uneven relationship, caretaker and caregiver. But who holds the power, the upper hand when Siegl, bookish and naive, hires Alma, barely literate, as his assistant? Attracted by her lack of literary pretension, and perhaps by his ability to chisel a polished gem from a discarded stone, Siegl has little understanding of the pent-up hatred his assistant carries.

Anti-Semitism plays a prominent role in the unlikely working relationship the play divulges. Somewhere in her youth, Alma picked up virulent Jew-hatred of the worse kind along with a belief in the Holocaust as a hoax. That Siegl, son of a Jewish refugee, built a career on fictionalizing the Holocaust experiences of his father's family rankles Alma.

The Tattooed Girl, dark, nearly gothic in novel form, is lighter, necessarily faster paced on stage. Director Vreeke draws an astonishing performance in particular from Michelle Shupe as Alma, the battered and abused wanderer who finds hope in the man who she would believe to be her worst foe, "the Jew professor Siegl," as she says.

Siegl, too, is suffering, not merely nor only from the trauma of never again attaining the critical acclaim he earned with his early literary success, but the pompous and erudite writer has become afflicted by a physical malady, something involving his deteriorating nervous system.

Whatever the physical cause, the previously independent gentleman must rely on a cane and the supportive hands of his assistant to ascend the daunting stairway, gorgeously designed to expand the theater's depth by designer Daniel Conway, in his book-filled mansion, located in or near an unnamed northeastern university town.

Shupe, who on Theater J's stage has grown in recent years into a skillful and perceptive character actress, here strips away layers of hatred and distrust that Alma thrusts forward to reveal this abused woman's inner vulnerability.

With her stringy blond hair and flatly unemotional western Pennsylvania twang, Shupe is sometimes a cipher in Susan Chiang's loose, gauzy skirts and sweaters. She wears those hideous skin defacements -- the tattoos -- as a sign of pain and shame, for they were forced on her when she was strung out.

As Siegl, Michael Russotto, another Theater J regular, hides much beneath his upper-crust exterior, which is equal parts gruff and oblivious, in particular to those he encounters who don't have his financial and educational assets.

Cam Magee makes a brief but memorable appearance as Siegl's overbearing but deeply jealous sister, Jet. And making a powerful Theater J debut, Christopher Browne plays Dmitri, Alma's sinister lowlife boyfriend, an abuser who takes in strays only to later strangle them.

Oates has spoken of writing The Tattooed Girl as a novel and a play simultaneously. Yet she chose different endings for each, demonstrating the malleability and continuity of the creative process.

The author discovered late in life her own family's Jewish history: Her grandmother, who immigrated to the United States in the 1890s, kept her religion hidden for fear of persecution. So the question arises: Can Oates' writing be characterized as distinctively Jewish?

In The Tattooed Girl, she grapples pointedly with anti-Semitism as it plays out in the Alma-Siegl relationship. But for Oates, anti-Semitism and victim-perpetrator relationships are part of the bigger picture that she wants audiences to draw from, particularly as the nation continues to heal from 9/11 and perpetrates a war abroad.

For Oates, Siegl's Jewishness, Alma's Jew-hatred and the evolving balance of power between the pair become at the play's core the crux of the matter.

The Tattooed Girl is onstage at the DCJCC through Feb. 20. are available by calling 800-494-8497.