Shame 2.0 with comments from the populace Shame 2.0 with comments from the populace by Einat Weizman directed by John Vreeke Hate

mail. Death threats. Intimidation. Incarceration. Artists under siege

and house arrest. This is happening. Now. This is Shame 2.0, a

blistering, documentary portrait ripped right from today’s headlines.

As Israelis and Palestinians work together in the face of government

censorship, cultural suppression, and Loyalty Oaths, we see the costs

on embattled artists in a conflict-ridden region unfold onstage. It is

a gripping snapshot of now, written in realtime.   Shame 2.0 Shame 2.0Part of Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival Mosaic Theater At the Atlas Performing Arts Center, Sprenger Theatre January 30—February 17, 2019 Photos from "Shame 2.0", with more throughout the reviews: (click to enlarge)

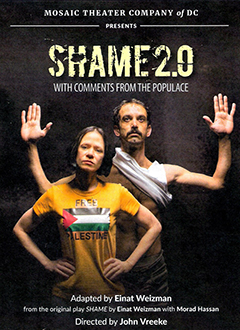

REVIEWS:  A work that goes to the heart of what's dangerous about dissident art Review by John Stoltenberg DC Metro Theater Arts “You have to be a good Arab,” says Morad Hassan of the stigma he faces trying to have a career as an Arab actor in Israel—the very country where, he says, “we are the Jews of the Jews.”  “FREE

PALESTINE,” says the T-shirt worn by Israeli playwright Einat

Weizman—the very shirt, imprinted with the PLO flag, that prompted a

torrent of online abuse when a photo of her in it appeared on a popular

internet site. “FREE

PALESTINE,” says the T-shirt worn by Israeli playwright Einat

Weizman—the very shirt, imprinted with the PLO flag, that prompted a

torrent of online abuse when a photo of her in it appeared on a popular

internet site. In SHAME 2.0 just opened at Mosaic, these two scrappy artist-activists from the front lines of a culture war tell their extraordinary and instructive stories. In form, the show is a vivid theatrical scrapbook—a patchwork of monologues, TV news clips, projections, citations from cyberhate, vitriolic voicemails. In intent, SHAME 2.0 is Einat Weizman’s and Morad Hassad’s DIY docudrama of how they tried to make art to make change and what it cost them. In effect, SHAME 2.0 goes to the heart of what’s dangerous about dissident art. The backstage history of SHAME 2.0 is a drama in itself. Weizman adapted it from an earlier work that she and Hassan co-authored titled SHAME. Mosaic Founding Artistic Director Ari Roth—who met them in Israel when both were acting in a play that Mosaic would later stage as The Return—imported the project and for a time was announced as a co-adapter. But, as Roth explains in his program note, that changed: A funny thing happened on the way to the workshopping of Shame 2.0—I began losing control of a story that wasn’t mine. And by the middle of the second week of rehearsals, a script I believed was approaching its definitive state, turned out not to be: not in the eyes of the collaborators who mattered most.  Now

onstage as part of Mosaic’s Voices from a Changing Middle East

Festival—in what’s deftly called a world premiere workshop production,

directed gingerly by John Vreeke—SHAME 2.0 had conflicts during

rehearsals so serious there was talk of calling it off. Luckily for DC

theatergoers and theater makers who prefer art not stripped of

principles, the show did go on. Now

onstage as part of Mosaic’s Voices from a Changing Middle East

Festival—in what’s deftly called a world premiere workshop production,

directed gingerly by John Vreeke—SHAME 2.0 had conflicts during

rehearsals so serious there was talk of calling it off. Luckily for DC

theatergoers and theater makers who prefer art not stripped of

principles, the show did go on.Hassan, an appealingly dexterous actor, plays himself with great charm. For the first half hour or so, he regales us with stories of indignity from his life as a working actor in Israel’s politically fraught theater scene. As the only Arab student in Hebrew University, for instance, he finds out no Palestinian writers are taught. He is type-cast in Arab roles (thus “You have to be a good Arab”), then gets a gig in Waiting for Godot playing a Palestinian speaking Hebrew. The pinnacle of his thespian identity disjunction (call it TID) is his turn as Shakespeare’s Shylock. But in an amazing turnabout, Hassan delivers Shylock’s famous speech… Up next for another half hour or so is the very principled Weizman. Though portrayed here by Colleen Delany with fetching conviction, Weizman was in real-life widely reviled for her beliefs. Her story interweaves two trenchant threads. One is what happened to her when her photograph in that T-shirt prompted a horrendous online attack of hate speech, some of which tweets and Facebook posts are incorporated graphically into the show (hence “comments from the populace”). Delany as Weizman hands out a dozen cards to audience members and at points asks them to be read aloud. “Thank you for…playing along,” Delany/Weizman says wryly. Even for someone familiar with the cesspool of misogynist invective in cyberspace, hearing ordinary folks give voice in public to such real-life insults can be unsettling. “Thank you,” she says graciously after each. Weizman’s other narrative is about state suppression of dissident Palestinian artists in Israel. For instance, funding for Israel’s only Arab-speaking theater, Al-Midan Theater in Haifa, was summarily frozen after it staged a play alleged to incite terrorism (it didn’t; it was simply a docudrama about a prisoner convicted on dubious grounds of killing an Israeli soldier). To amplify and personalize this censorship, a third character has been added for the American run: Israel’s current culture minister, Miri Regev, the stylish right-winger who decreed the funding cutoffs and required that Arab artists sign a pro-Israel loyalty oath. Regev is the heavy of the story, and it’s a challenging role to play at all likably, but Lynette Rathnam in it succeeds with remarkable aplomb.  Introducing

the play on opening night, Associate Artistic Director Victoria Murray

Baatin explained that this workshop would be a “stripped down” version.

Nothwithstanding that disclaimer, the production was very well

outfitted by a creative team that included Set Designer Jonathan Dahm

Robertson, Lighting Designer Brittany Shemuga, Costume Designer Brandee

Mathies, Projections Designer Dylan Uremovich (whose rear-wall

animations much enhanced the storytelling), Sound Designer David Lamont

Wilson (whose audio clips from hate tweets also propelled the story),

and Sound Engineer Robert Garner (whose mic’ing of the cast gave

appreciated clarity to each speech). Introducing

the play on opening night, Associate Artistic Director Victoria Murray

Baatin explained that this workshop would be a “stripped down” version.

Nothwithstanding that disclaimer, the production was very well

outfitted by a creative team that included Set Designer Jonathan Dahm

Robertson, Lighting Designer Brittany Shemuga, Costume Designer Brandee

Mathies, Projections Designer Dylan Uremovich (whose rear-wall

animations much enhanced the storytelling), Sound Designer David Lamont

Wilson (whose audio clips from hate tweets also propelled the story),

and Sound Engineer Robert Garner (whose mic’ing of the cast gave

appreciated clarity to each speech).In the end, what stands out in SHAME 2.0 is Einat Weizman’s and Morad Hassan’s insistence on their right to their own voice in art and their persistence in the face of prejudice and vilification. Even behind the scenes, as the script intimates, they did not quit advocating for what they needed to say and how they needed to say it. As the slogan “Nothing about us without us!” gains traction in American theater, Mosaic is again at the cutting, and very complex, edge. Anyone who cares about art that matters must not miss this inspiring instance of what makes theater worth it—and what makes making such theater hard. Review by John Stoltenberg DC Metro Theater Arts  This documentary play about Israeli artists is a raw, uneasy 80 minutes Review by Nelson Pressley Washington Post theater critic The psychological wounds gape wide in “Shame 2.0,” a documentary play about Israeli artists in conflict with their government and a verbally brutal public. One of the principals — Arab Palestinian actor Morad Hassan — is in the lean cast of three at Mosaic Theater, narrating some of his own experiences.  It’s

a raw, uneasy 80 minutes. “Shame 2.0,” adapted by Israeli playwright

Einat Weizman from the original play “Shame,” by Weizman and Hassan, is

a deeply personal account, performed in a deceptively tranquil tone.

Hassan is low-key as he describes his position as an Arab actor with

dwindling opportunities in Israel, ironically hitting a peak playing

the Jewish moneylender Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice.” Colleen

Delany is similarly coolheaded as Weizman, whose drama “Prisoners of

the Occupation,” plus a “Free Palestine” T-shirt, drew the wrath of

Culture Minister Miri Regev (played by Lynette Rathnam and, for good

measure, also seen in projected news footage). It’s

a raw, uneasy 80 minutes. “Shame 2.0,” adapted by Israeli playwright

Einat Weizman from the original play “Shame,” by Weizman and Hassan, is

a deeply personal account, performed in a deceptively tranquil tone.

Hassan is low-key as he describes his position as an Arab actor with

dwindling opportunities in Israel, ironically hitting a peak playing

the Jewish moneylender Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice.” Colleen

Delany is similarly coolheaded as Weizman, whose drama “Prisoners of

the Occupation,” plus a “Free Palestine” T-shirt, drew the wrath of

Culture Minister Miri Regev (played by Lynette Rathnam and, for good

measure, also seen in projected news footage).That measured demeanor is countered by verbatim invective and vengeance as the government defunds theaters and campaigns against plays. A segment of the public vilifies Weizman, in particular, as an anti-Israel supporter of murderers and terrorists. (Weizman was in the audience Thursday night at the Atlas Performing Arts Center as Delany played her, with members of the audience reading aloud some of the vitriol she has endured.)  The

subtitle of “Shame 2.0” is “With Comments From the Populace,” and those

indisputably savage messages certainly throw the friction into stark

relief. Everything about this project is uneasy, though. The densely

packed, information-heavy presentation is a workshop at Mosaic, meaning

it had a long preview period and is performed on a minimal set (though

Dylan Uremovich’s news projections bring polish and urgency to director

John Vreeke’s blunt staging). Artistic Director Ari Roth notes in the

program that this U.S. adaptation was difficult at Mosaic: Creative

differences cropped up even among allies. And of course Mosaic was born

of related disputes over how to represent Palestinian issues in

Jewish-supported art, as Roth was fired from D.C.’s Theater J four

years ago. The

subtitle of “Shame 2.0” is “With Comments From the Populace,” and those

indisputably savage messages certainly throw the friction into stark

relief. Everything about this project is uneasy, though. The densely

packed, information-heavy presentation is a workshop at Mosaic, meaning

it had a long preview period and is performed on a minimal set (though

Dylan Uremovich’s news projections bring polish and urgency to director

John Vreeke’s blunt staging). Artistic Director Ari Roth notes in the

program that this U.S. adaptation was difficult at Mosaic: Creative

differences cropped up even among allies. And of course Mosaic was born

of related disputes over how to represent Palestinian issues in

Jewish-supported art, as Roth was fired from D.C.’s Theater J four

years ago.Still, it’s valuable to get this report from Israel’s front lines. As you watch the grim Hassan’s self-reenactment and the desert-dry Delany as Weizman, what comes through is the effort to keep this telling calm, along with the frustrations of being activist artists in ferociously contested territory. A recent episode of NPR’s science podcast “Hidden Brain” used Israelis and Palestinians to illustrate how traumatized people have extraordinary difficulty hearing anything human about their “enemies.” That’s what you see in “Shame” — so many scars. Review by Nelson Pressley Washington Post theater critic  Political and Cultural Tensions Arise in Mosaic's Shame 2.0 The pieces of documentary theater stir up debates about political interference in art. Review by Ian Thal Washington City Paper Mosaic Theater Company’s production of Shame 2.0 begins when its co-author, the actor Morad Hassan, walks onto an unadorned stage. Behind him is a photographic projection (the first of many by Dylan Uremovich) displaying the sign for Al-Midan, Israel’s state-funded Arabic-language theater. The surrounding architecture is distorted in the reflective glass of the shopping mall where the theater makes its home — perhaps this is a metaphor for the relationship between art and society.  Hassan

then describes the night in 2015 when, an hour before a performance of

the play A Parallel Time, protesters surrounded Al-Midan. The play was

based on the life of Walid Daka, a Palestinian with Israeli citizenship

currently serving a life sentence for his involvement in the abduction

and murder of an Israeli soldier, Moshe Tamam. Daka claims to be a

pacifist and peripheral to the plot for which he was convicted, but

without seeing the play, protesters contended that it celebrated

terrorism, and government funding was yanked from the production. Hassan

then describes the night in 2015 when, an hour before a performance of

the play A Parallel Time, protesters surrounded Al-Midan. The play was

based on the life of Walid Daka, a Palestinian with Israeli citizenship

currently serving a life sentence for his involvement in the abduction

and murder of an Israeli soldier, Moshe Tamam. Daka claims to be a

pacifist and peripheral to the plot for which he was convicted, but

without seeing the play, protesters contended that it celebrated

terrorism, and government funding was yanked from the production. Shame 2.0’s authors take Daka at his word but do not seek to re-adjudicate his trial; he is largely peripheral to Hassan and his Jewish-Israeli co-author Einat Weizman’s experiences as artists in a country whose political culture has lurched to the right. Hassan did not set out to be an activist; he was simply a young man from Galilee who, instead of joining the family business making sweets, decided to study acting. At his day job as a bartender, he might deliver a favorite monologue by Israeli absurdist Hanoch Levin to his bar patrons. Later, he recounts his experience as a Palestinian-Israeli actor playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, concluding that the Palestinians “are the Jews of the Jews.”  The

second half of this play is Weizman’s story. In 2006, Weizman,

portrayed on stage by Colleen Delany, was photographed wearing a yellow

“Free Palestine” T-shirt that her sister picked up on a lark while

traveling in India. Years later, Weizman, now working as a documentary

playwright, wonders if her decision to leave the house in the shirt can

be attributed to na´vetÚ, irony, or impulsivity. Comments come in

harassing phone messages and hate mail—some graphically describing

sexual abuse at the hands of terror cells she allegedly sympathizes

with. The photo resurfaces on social media after she criticizes Israeli

conduct during the 2014 Gaza Conflict and so does the harassment. Where

Hassan seems to relish his stage persona, Delany’s performance appears

more constrained. Perhaps because Weizman was present for the

workshopping process at Mosaic, her section comes across as more of a

lecture with theatrical elements than a play. The

second half of this play is Weizman’s story. In 2006, Weizman,

portrayed on stage by Colleen Delany, was photographed wearing a yellow

“Free Palestine” T-shirt that her sister picked up on a lark while

traveling in India. Years later, Weizman, now working as a documentary

playwright, wonders if her decision to leave the house in the shirt can

be attributed to na´vetÚ, irony, or impulsivity. Comments come in

harassing phone messages and hate mail—some graphically describing

sexual abuse at the hands of terror cells she allegedly sympathizes

with. The photo resurfaces on social media after she criticizes Israeli

conduct during the 2014 Gaza Conflict and so does the harassment. Where

Hassan seems to relish his stage persona, Delany’s performance appears

more constrained. Perhaps because Weizman was present for the

workshopping process at Mosaic, her section comes across as more of a

lecture with theatrical elements than a play.Shame 2.0 (the version presented at Mosaic significantly expands upon the original play) is structured as a diptych. The stories of its two authors run parallel, sharing an antagonist in Minister of Culture and Sport Miri Regev, played by Lynette Rathnam (and often accompanied by a video projection of the real Regev), a retired brigadier general who served as a spokesperson for the IDF during the 2006 Lebanon War.  American

artists are often envious of their counterparts in countries that have

a stronger tradition of public funding for the arts. Israel, due to its

founders’ socialist leanings, has a long history of state and

municipally funded theaters — but as Regev demonstrates, that funding

comes with leverage. International attempts to boycott Israeli culture

alarm her and Regev takes a more militant line than her predecessors.

Weizman becomes a convenient excuse to exercise her ministry’s “freedom

of funding” by cutting off theaters and festivals that present artists

she regards as “disloyal.” American

artists are often envious of their counterparts in countries that have

a stronger tradition of public funding for the arts. Israel, due to its

founders’ socialist leanings, has a long history of state and

municipally funded theaters — but as Regev demonstrates, that funding

comes with leverage. International attempts to boycott Israeli culture

alarm her and Regev takes a more militant line than her predecessors.

Weizman becomes a convenient excuse to exercise her ministry’s “freedom

of funding” by cutting off theaters and festivals that present artists

she regards as “disloyal.” Shame 2.0 is a messy play with a messy development process that shows on stage—early press credited Mosaic Artistic Director Ari Roth with the adaptation and he freely admits he had to surrender that role to the original artists over the course of the workshop—but it is also fitting with the unfinished subject at its center. As with much documentary theater, its value is the potentially heated debates that occur after leaving the auditorium. Non-profit theaters in America may be free from the political interference Weizman and Hassan describe, but our cultural economy creates its own fulcra of leverage. Review by Ian Thal Washington City Paper  Shame 2.0 with Comments from the Populace. Truth on stage Review by Susan Galbraith DC Theatre Scene  Billed

as a workshop production to which the press was invited, Mosaic Theater

Company’s Shame 2.0 with Comments from the Populace opened Thursday

night with all hands on deck in solidarity and much marketing

trumpeting it as a “DC world premiere” of docu-theater. Around the

edges, however, and in the margins of conversations introducing the

play, it became all too clear that the process had proved brutal and

that, from the battleground with all lines drawn, the creative team had

emerged in pyrrhic victory at best, with everyone still limping and

bleeding. Billed

as a workshop production to which the press was invited, Mosaic Theater

Company’s Shame 2.0 with Comments from the Populace opened Thursday

night with all hands on deck in solidarity and much marketing

trumpeting it as a “DC world premiere” of docu-theater. Around the

edges, however, and in the margins of conversations introducing the

play, it became all too clear that the process had proved brutal and

that, from the battleground with all lines drawn, the creative team had

emerged in pyrrhic victory at best, with everyone still limping and

bleeding.There is a kind of irony in the fact that the show was nearly cancelled, as Shame 2.0 is about, on the one hand, artistic censorship in Israel and lack of equity between the Jewish state power and its citizens who run the country and control the cultural as well as the political scene, and, on the other, the Palestinians who live there, marginalized and under brutal occupation. The play also holds a mirror up to our own current raging debate about “Who gets to tell the story?”  Artistic

Director Ari Roth is no newcomer when it comes to tackling difficult

subject matter with his theatrical choices. He is committed to

cross-cultural engagement and is experienced in the messy process that

is most often involved. Artistic

Director Ari Roth is no newcomer when it comes to tackling difficult

subject matter with his theatrical choices. He is committed to

cross-cultural engagement and is experienced in the messy process that

is most often involved.In presenting Nicholas Wright’s A Human Being Died Last Night, Roth gave us another dramatized transcript of several conversations that took place between a psychologist, Gobodo-Madikizela, and Eugene de Kock in Pretoria’s Central Prison between 1997-2002. The work forced the audience to bear witness and, in some sense, weigh in as both jury and judge. Another Mosaic production that had been shocking to some and provoked much post-performance debate was The Return by Hannah Eady Edward Mast about an Israeli woman who had nearly destroyed a Palestinian man she’s had an affair with in her convenient lie about being raped, playing into stereotype crime profiles and racist hatred. Strong stuff and disturbing, but very worth looking at and trying to understand. John Vreeke had directed that play, and he did it masterfully.  In

this case, Roth has invited the co-authors Einat Weizman, a Jewish

playwright committed to works of social justice and activism, and Morad

Hassan, a Palestinian actor living and working in Israel, to re-work

and expand their play. In

this case, Roth has invited the co-authors Einat Weizman, a Jewish

playwright committed to works of social justice and activism, and Morad

Hassan, a Palestinian actor living and working in Israel, to re-work

and expand their play.The question is, was this process worth it? The second question will probably be best answered by the artists and company after the dust settles. Since the production was, after mounting tensions and disagreements, turned back to “the primary authorship,” we will never perhaps know what the original intention was. As a theatrical experience, it is, in truth, not very satisfying. Part of the problem, to my taste, was that the two lead performers were uneven in their investment in the material, and not so much unequal in talent as simply coming from two entirely different worlds and styles of theater-making.  Morad

Hassan is a Palestinian actor playing himself. As such, he

carries all the moral authority in this story. Moreover, from the

moment he walks downstage center, he grabs and holds the audience’s

attention. He shapes his narrative, moving with ease between

comedy and seriousness. With his small, wiry body and seemingly

oversized hands and sneakered feet, he is a physical performer who

knows how to use his instrument expressively. Hassan projects

vulnerability and sometimes self-deprecating humor, but hardly the

projection of someone deemed a terrorist by a country like ours in the

throes of creating false narratives of “us vs. them” Hassan is a truly

accomplished actor whose every gesture and every step are given weight

and presence. Morad

Hassan is a Palestinian actor playing himself. As such, he

carries all the moral authority in this story. Moreover, from the

moment he walks downstage center, he grabs and holds the audience’s

attention. He shapes his narrative, moving with ease between

comedy and seriousness. With his small, wiry body and seemingly

oversized hands and sneakered feet, he is a physical performer who

knows how to use his instrument expressively. Hassan projects

vulnerability and sometimes self-deprecating humor, but hardly the

projection of someone deemed a terrorist by a country like ours in the

throes of creating false narratives of “us vs. them” Hassan is a truly

accomplished actor whose every gesture and every step are given weight

and presence.Local actor Colleen Delany delivered a flatter performance, her arms hanging as if lifeless at her sides. I never believed she could have carried in her the fiery furnace of someone who risked “crossing over to the other side” time and again, taking the heat of being called a traitor and risking her reputation and, even at times her life, to keep exposing the stories of injustice to the Palestinians. Delany’s style was dialed down,to more like a television talking-head. (Well, perhaps this was intentional, as Weizman had been a TV and Film personality.) Ultimately, the two lead characters felt mismatched. Lynette Ratham played the live impersonation of Miri Regev, the Israeli Minister of Culture and Sports. She valiantly competes with the supersize video projections of this woman and communicates the translated diatribe against the Palestinians and their supporters. She invokes the role as Voice of the Far Right, demonstrating Israel’s heavy-handed suppression of dissident art. But having Ratham, as the on stage double, perform with Regev’s glamorous TV looks looming behind the actress is tough. Further, Regev is a curious character in the script, neither fully realized nor made into a cartoon-like cameo. Has something been excised or lost in translation? Director Vreeke has done yeoman’s duty. You could almost feel him wanting to hold the center together throughout the evening. There might yet be a play in the journey.  What

remains of this play is a montage and patching together of monologues,

news clips, and crude bleep-filled diatribes from social media.

Jonathan Dahm Robertson has created a world with his series of

projections of live political footage that brings clarity to the

struggle in Israel for equity. What

remains of this play is a montage and patching together of monologues,

news clips, and crude bleep-filled diatribes from social media.

Jonathan Dahm Robertson has created a world with his series of

projections of live political footage that brings clarity to the

struggle in Israel for equity.At one point the action stopped, and big cards were handed out to audience members who volunteered to read. Calling on audience participation always presents theatrically risky business. As the individual readers were not actors or able to project or shape spoken arguments, and some of the statements being quite long, any sense of the evening’s real dramatic propulsion was halted. This process was clearly of great political importance to the play’s agenda, even reflected in the title, adding to the collected evidence of the assault on Weizman in social media. Sadly, much of the text was garbled or lost entirely.  Mostly, I longed for the complexity and nuance of characters and story that I have experienced in many other shows at Mosaic. There were moments that played and broke the tension then skewered the audience effectively. Hassan jokes “We are Jews of the Jews,” delivering the line like an accomplished stand up comedian, Shortly after he launches into lines from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice from a production where (irony again) he played the Jew himself “If you prick us, do we not bleed?” I wanted more of this hefty resonance. The last word on this production must be given to Roth, who faced a most difficult choice in a production where the artists seem to have mutinied. He made his exit, recognizing that “we’re working with frontline artist-activists from a war zone…we’ve offered an integrity of voice as articulated by the artists closest to those frontlines. Few people are as brave or fierce in their documentary-based pursuits to give voice to the silenced as Einat, and her partnership with Morad is to be respected, and has been.” Review by Susan Galbraith DC Theatre Scene |