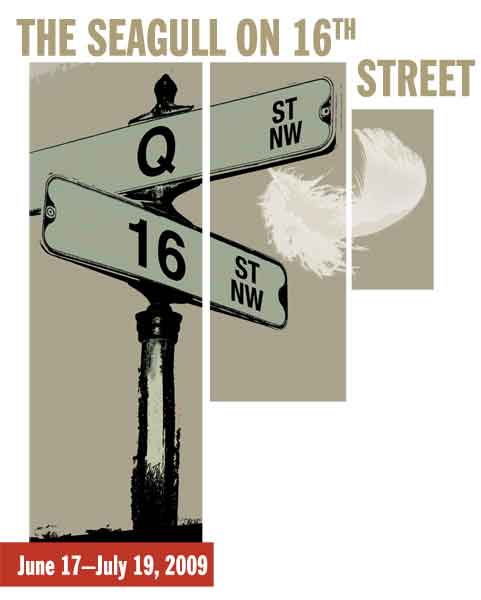

The Seagull on

16th Street

by Anton Chekhov

adapted by Ari Roth, based on a

translation by Carol Rocamora

directed by John Vreeke

Youth is envied, challenged and mortally wounded in this

classic by the great Russian master. Inspired by Louis Malle's Vanya on

42nd Street, our own 16th Street provides the stage for a journey back

to the Russian countryside in this tale of love and loss, with laughs

and heartbreak. Featuring Alexander Strain, Naomi Jacobson, Jerry

Whiddon and J. Fred Shiffman.

June 17th through

July 19th, 2009, at Theatre J, Washington DC

REVIEW QUOTES:

What emerges under the confident direction of John Vreeke (who helmed Forum’s much-loved Last Days of Judas Iscariot last year) is crisp, funny, and ably performed. It’s also inflected with an extra shtikl of comic energy by artistic director Ari Roth’s adaptation. - Washington CIty Paper

John Vreeke’s direction is crisp with a speedy sense of time even with a stage clock in the audience’s view stuck at 8 PM. He has blocked this work so that the stage is filled not just with objects but with life.

- Potomac Stages

Director John Vreeke astutely goes with a more contemporary vibe by unleashing the cast like a spirited team of horses to provide a more lively interpretation than usually seen, and the actors take full advantage of the opportunity. - DC Theatre Scene

Playwright Roth's rejigging of the script, is helped along immensely by director John Vreeke, who understands that while Chekhov deliberately labeled this work a comedy, tragedy is never distant.

- Washington Jewish Week

Director John Vreeke has assembled a cast of solid actors, some of whom...strike a winning connection with Chekhov. - Washington Post

FULL REVIEWS

Chekhov brings the funny at Theater J

By Glen Weldon

June 24, 2009

As much as the name

Anton Chekhov conjures images of bored, po-faced Russians dithering

over samovars and parting the air with long, wet sighs, the guy knew

how to do funny, and 2009 is giving D.C. audiences a couple chances to

see it. In January, the Washington Shakespeare Company mounted a

downright slapstick Cherry Orchard with intriguing, if mixed, results.

Now Chekhov’s Seagull—the consumptive Cossack’s first and most

meticulous examination of despair and distraction among the Russian

gentry—is getting fed through the comedy filter at Theater J.

As much as the name

Anton Chekhov conjures images of bored, po-faced Russians dithering

over samovars and parting the air with long, wet sighs, the guy knew

how to do funny, and 2009 is giving D.C. audiences a couple chances to

see it. In January, the Washington Shakespeare Company mounted a

downright slapstick Cherry Orchard with intriguing, if mixed, results.

Now Chekhov’s Seagull—the consumptive Cossack’s first and most

meticulous examination of despair and distraction among the Russian

gentry—is getting fed through the comedy filter at Theater J. What emerges under the confident direction of John Vreeke (who helmed Forum’s much-loved Last Days of Judas Iscariot last year) is crisp, funny, and ably performed. It’s also inflected with an extra shtikl of comic energy by artistic director Ari Roth’s adaptation.

Inspired by Louis

Malle’s film Vanya on 42nd Street, Roth’s

script has fun blurring the lines between actor and role, production

and play, contemporary culture and 1898 Russia. The play’s famous

opening exchange—in which the lovesick Masha (Tessa Klein) explains

that she wears black because “I am in mourning for my life”—remains

intact, but the performers sidle up to it gradually, and Masha’s

black-lace-and-leather wardrobe is more Dead Can Dance than dacha.

(Roth’s attempt to overlay the play with Jewish themes is less

successful, because such affinities can’t simply be asserted if they’re

to carry real weight. To work as Roth intends, they’d need to be woven

even more thoroughly into the warp and woof of the text than they have

been here.)

Inspired by Louis

Malle’s film Vanya on 42nd Street, Roth’s

script has fun blurring the lines between actor and role, production

and play, contemporary culture and 1898 Russia. The play’s famous

opening exchange—in which the lovesick Masha (Tessa Klein) explains

that she wears black because “I am in mourning for my life”—remains

intact, but the performers sidle up to it gradually, and Masha’s

black-lace-and-leather wardrobe is more Dead Can Dance than dacha.

(Roth’s attempt to overlay the play with Jewish themes is less

successful, because such affinities can’t simply be asserted if they’re

to carry real weight. To work as Roth intends, they’d need to be woven

even more thoroughly into the warp and woof of the text than they have

been here.)  The parallels that

do work, and work well, are visual and emotional: Note how similarly

both Naomi Jacobsen’s Arkadina and Alexander Strain’s Treplev evince

their soaring neediness—Vreeke has mother and son literally cling to

their respective paramours, choking them like creeper vines. Jacobsen

and Strain fill out only two slots in what’s pretty much a Justice

League roll call of D.C. performers: Jerry Whiddon’s rumpled Trigorin;

J. Fred Shiffman’s effortlessly empathetic Doctor Dorn; a compassionate

Nanna Ingvarsson; a commanding Brian Hemmingsen.

The parallels that

do work, and work well, are visual and emotional: Note how similarly

both Naomi Jacobsen’s Arkadina and Alexander Strain’s Treplev evince

their soaring neediness—Vreeke has mother and son literally cling to

their respective paramours, choking them like creeper vines. Jacobsen

and Strain fill out only two slots in what’s pretty much a Justice

League roll call of D.C. performers: Jerry Whiddon’s rumpled Trigorin;

J. Fred Shiffman’s effortlessly empathetic Doctor Dorn; a compassionate

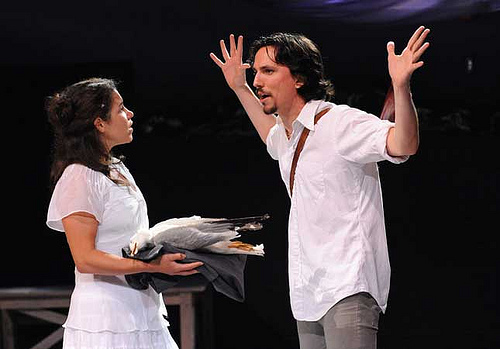

Nanna Ingvarsson; a commanding Brian Hemmingsen. Nina (Veronica del Cerro), the provincial girl who gets caught up and nearly destroyed by the play’s events, never emerges clearly here: Del Cerro’s fine in the early going, when Nina is filled with hope and desperate dreams. But when the character appears at the end of the play, she has been overmatchedus t by life—she is fragile, shattered, an exposed nerve. Del Cerro instead comes across as mildly diffuse and distracted; as a result, the play’s famous climax, which should feel inevitable, can’t arrive with the requisite force. Even so, this Seagull is lively, solidly built and frequently funny—and productions of Chekhov that achieve that particular trifecta are rare indeed.

This 'The Seagull' is a gutsy, distinctive turn

Reviewed June 27 by David Siegel

This is an appealing

work for those immersed in the esteemed Anton Chekhov’s oeuvre and who

want to see a contemporary world premiere adaptation with a rather

unique twist. This is no half-hearted variation of costume changes and

frothy accents. This The Seagull is a gutsy, distinctive turn that

brings forth issues of faith that Ari Roth found present in Chekhov’s

century old original. In his adaptation, Roth superimposes matters

regarding the Jewish faith and the struggles of prominent characters to

either reconnect with their former religion or continue on their path

to assimilation and integration into society. This newly-minted theme

is overlaid on Chekhov’s bracing work regarding artistic creativity as

well as the consequences of mismatches of love. Does the adaptation

work? More so for Chekhov aficionados who want to size up an

interloper’s efforts. The needy diva and verbally bullying mother is

played with a flip of the hand by Naomi Jacobson. She lives for the

external validation of audience applause. Alexander Strain, her

extremely sensitive and psychologically unmoored playwright son is

inevitably outwitted or outmaneuvered and not just by Jacobson.

Surrounding them are assorted others, each with an emotionally unstable

life story that captures the essence of people who have little to keep

themselves vibrant unless “an other” is present to shine a light or

provide warm hugs. The underlying original, The Seagull (1896), still

connects with its dark humor; a son crushed, feckless males hurting

impressionable young women and languid, dreamy people grappling with

their needy natures. This is ultimately a heady rendering of drama

kings and queens living self-indulgent lives.

This is an appealing

work for those immersed in the esteemed Anton Chekhov’s oeuvre and who

want to see a contemporary world premiere adaptation with a rather

unique twist. This is no half-hearted variation of costume changes and

frothy accents. This The Seagull is a gutsy, distinctive turn that

brings forth issues of faith that Ari Roth found present in Chekhov’s

century old original. In his adaptation, Roth superimposes matters

regarding the Jewish faith and the struggles of prominent characters to

either reconnect with their former religion or continue on their path

to assimilation and integration into society. This newly-minted theme

is overlaid on Chekhov’s bracing work regarding artistic creativity as

well as the consequences of mismatches of love. Does the adaptation

work? More so for Chekhov aficionados who want to size up an

interloper’s efforts. The needy diva and verbally bullying mother is

played with a flip of the hand by Naomi Jacobson. She lives for the

external validation of audience applause. Alexander Strain, her

extremely sensitive and psychologically unmoored playwright son is

inevitably outwitted or outmaneuvered and not just by Jacobson.

Surrounding them are assorted others, each with an emotionally unstable

life story that captures the essence of people who have little to keep

themselves vibrant unless “an other” is present to shine a light or

provide warm hugs. The underlying original, The Seagull (1896), still

connects with its dark humor; a son crushed, feckless males hurting

impressionable young women and languid, dreamy people grappling with

their needy natures. This is ultimately a heady rendering of drama

kings and queens living self-indulgent lives.

Storyline: Youth is envied, challenged and mortally wounded in this tale of lovelorn artists, civil servants and household workers. In a new adaptation of Chekhov's play, there is a contemporary portal though which the production journeys back in time to the Russian countryside revealing the clash between mother and son affecting others.

Anton Chekhov (1860–1904) was a pre-eminent Russian playwright and a major short-story writer. He produced four theater classics including Uncle Vanya (1897), Three Sisters (1901), and The Cherry Orchard (1904) as well as The Seagull. We will never know what Chekhov would think of this adaptation, but he did give a nod with Seagull lines such as “we need new forms of expression” matched with “in all the universe nothing remains permanent and unchanged but the spirit.” Rather than reflecting upon the oft-revived playwright Chekhov, your reviewer notes that adapter Roth wrote in length regarding Theater J’s “first foray into fully producing classical work” and the liberties taken to connect with the Theatre J mission to “celebrate the distinctive urban voice and social vision that are part of the Jewish cultural legacy.”

John Vreeke’s direction is crisp with a speedy sense of time even with a stage clock in the audience’s view stuck at 8 PM. He has blocked this work so that the stage is filled not just with objects but with life. The cast glides and slides, working with their upper bodies, projecting their inner commotions with a tad of a knowing grin. A curtain shimmies as if wind is blowing, a shimmering lake is projected at the rear of the set and later even a visibly dead stuffed bird appears.

Naomi Jacobson’s

manipulative, self-absorbed Arkadina is the centerpiece; she willfully

pulls focus away from anyone who dares take her spotlight. She is a

bundle of waving dismissive arms, showering trivializing glances at

Alexander Strain’s attempts to live his own dream even as he surrenders

to her seemingly innocent hugs. Yet she does not seem to fill the stage

or suck out the air with her presence. Strain is artsy sensitive with

his struggling soul visible, finally gaining control with one final act

of off-set uncoupling from Jacobson after a showy bit of frustration

when he has the stage to himself. It is his journey into forgotten

Jewish roots that is the crux of the Roth adaptation that is met with

disdain and derision as his character evolves. J. Fred Shiffman is the

generally cheerful doctor who has lived a full life and still can turn

heads. He has the most realized sense of decency toward others though

he projects an almost disengaged manner. Veronica del Cerro is the

spirited, innocent who describes herself as a seagull, wanting freedom

to do as she desires. She is undone by her ga-ga reactions to the

celebrities she meets leading to her loss of youthful spotlessness …

beaten down by the stronger and less caring. Jerry Whiddon is the

dreamy playwright who is an object of desire by women who find his

frailness and words appealing. Tessa Klein is a brooding Masha; weary

and self-pitying living her life in mourning even before mourning is

required. Brian Hemmingsen and Nanna Ingvarsson add working class bite.

Naomi Jacobson’s

manipulative, self-absorbed Arkadina is the centerpiece; she willfully

pulls focus away from anyone who dares take her spotlight. She is a

bundle of waving dismissive arms, showering trivializing glances at

Alexander Strain’s attempts to live his own dream even as he surrenders

to her seemingly innocent hugs. Yet she does not seem to fill the stage

or suck out the air with her presence. Strain is artsy sensitive with

his struggling soul visible, finally gaining control with one final act

of off-set uncoupling from Jacobson after a showy bit of frustration

when he has the stage to himself. It is his journey into forgotten

Jewish roots that is the crux of the Roth adaptation that is met with

disdain and derision as his character evolves. J. Fred Shiffman is the

generally cheerful doctor who has lived a full life and still can turn

heads. He has the most realized sense of decency toward others though

he projects an almost disengaged manner. Veronica del Cerro is the

spirited, innocent who describes herself as a seagull, wanting freedom

to do as she desires. She is undone by her ga-ga reactions to the

celebrities she meets leading to her loss of youthful spotlessness …

beaten down by the stronger and less caring. Jerry Whiddon is the

dreamy playwright who is an object of desire by women who find his

frailness and words appealing. Tessa Klein is a brooding Masha; weary

and self-pitying living her life in mourning even before mourning is

required. Brian Hemmingsen and Nanna Ingvarsson add working class bite.

The Theatre J stage is decked out in weathered grey lumber given a sense of the sun bleached outdoors. Chairs, desks and a small cupboard are moved about to give a sense of time and seasonal changes; the lighting design producing the cold feel of an autumn storm. Costumes are not so much of a period, but of a class; no tattered clothes, but of the natty bourgeoisie and arty set impeccably dressed. Even those of lesser classes are not unkempt. Snippets of love songs from the 1950’s onward are sung by several actors to push feelings of unrequited love to the fore.

Adapted by Ari Roth from the play by Anton Chekhov. Translation by Carol Rocamora. Directed by John Vreeke. Design: Misha Kachman (set and costumes) Dan Covey (lights) Matt Nielson (sound) Stan Barouh (photography) Kate Kilbane (stage manager). Cast: Veronica del Cerro, Cesar A. Guadamuz, Brian Hemmingsen, Nanna Ingvarsson, Naomi Jacobson, Tessa Klein, Mark Krawczyk, Stephen Patrick Martin, Jason McCool, J. Fred Shiffman, Alexander Strain, Jerry Whiddon.

The Seagull on 16th Street - A new perspective on the drama

By Steven McKnight

June 25, 2009

It takes chutzpah to

write new dialogue for Chekhov’s classic The Seagull and to insert

Russian Jewish themes that didn’t exist in the original. While

the setting and basic plot remain the same, Theater J’s The Seagull on

16th Street adds dramatic conflicts over the extent to which several

characters, reimagined as Jewish, will cling to their heritage or seek

to assimilate into Russian society. Yet Ari Roth’s daring in

rewriting the play is a risk that pays off and rewards the audience

with a new perspective on the drama. This innovative adaptation

not only adds new ideas, but smoothly integrates them into the original

work to enhance the characters and augment some of Chekhov’s theme.

It takes chutzpah to

write new dialogue for Chekhov’s classic The Seagull and to insert

Russian Jewish themes that didn’t exist in the original. While

the setting and basic plot remain the same, Theater J’s The Seagull on

16th Street adds dramatic conflicts over the extent to which several

characters, reimagined as Jewish, will cling to their heritage or seek

to assimilate into Russian society. Yet Ari Roth’s daring in

rewriting the play is a risk that pays off and rewards the audience

with a new perspective on the drama. This innovative adaptation

not only adds new ideas, but smoothly integrates them into the original

work to enhance the characters and augment some of Chekhov’s theme.The new material appears from the inception of the play. The young dramatist Treplev (Alexander Strain) rebels against the melodramatic grand theatre that made his mother Arkadina (Naomi Jacobson) a famous actress. In classic Chekhov, Treplev merely hopes to pursue experimental theatre forms that draw more on abstract ideas and symbols. Roth’s version not only has Treplev wanting to create theatre that draws upon his Jewish heritage, but also has his mother crush Treplev by describing the play performed for friends and family at a Russian country home as “Hebraic tripe” (instead of decadent rubbish).

Similarly, Arkadina is clearly thrilled by big city life where she is acclaimed by the intelligentsia and a member of the artistic elite. She is pleased to have escaped rural Russia, as represented by her brother Sorin (Stephen Patrick Martin) and the bohemian collection of friends and servants at Sorin’s country estate. Roth further adds to the sense of separation by having Treplev embrace his Jewish heritage while Arkadina has hidden it as part of seeking assimilation into mainstream Russian society (again, an invention added to Chekhov’s text). At one point Arkadina proclaims that she is Russian, not Jewish. Interestingly, the nineteen-year-old aspiring actress who appears in Treplev’s work, Nina (Veronica del Cerro), claims she is not Jewish, she is an artist.

The overlay of Jewish heritage extends to smaller details as well. Characters discuss whether to maintain Sabbath rituals and toast each other with “L’chaim.” When Treplev shoots a seagull (an act which foreshadows future sadness in the play), Nina states that “Killing a living creature is not very Jewish.” Later Nina recites lines from a drama called “The Sabbath Bride.”

While the play’s characters and plotline may not depend upon the Jewish perspective added in this adaptation, the approach is certainly consistent with Chekhov’s writing. A son trying to live up to his mother’s expectations, artistic souls exploring the meaning of life amid existential angst, and discontented characters with unrequited romantic feelings can all easily be melded with the new elements that Roth introduces.

The character

relationships are unchanged.. Among the major

figures, Treplev is in love with Nina. Nina, in turn, longs for

the famous writer Trigorin (Jerry Whiddon), Arkadina’s consort.

The character

relationships are unchanged.. Among the major

figures, Treplev is in love with Nina. Nina, in turn, longs for

the famous writer Trigorin (Jerry Whiddon), Arkadina’s consort.Roth’s version does contain some variations in the mood of the piece. He attempts to keep the essentially wry mood, while updating the language and humor. This translation does not fully lend itself to the classic Chekhov atmosphere of wistful moments and meaningful silences.

As a result, director John Vreeke astutely goes with a more contemporary vibe by unleashing the cast like a spirited team of horses to provide a more lively interpretation than usually seen, and the actors take full advantage of the opportunity.

Strain’s rendition of the conflicted son with mother issues is more energetic and impatient and less whiny and self-defeating than standard portrayals. His Treplev is less overtly troubled and yet more convincing as a realistic character. It’s a strong and confident performance that helps define the new adaptation.

Similarly, del

Cerro brings an appealing vitality that adeptly captures

both the dewy optimism and the vulnerability of her character.

His spirit cannot be crushed by later off-stage elements (including an

unhappy affair), so her description near the end of the play of the joy

gained from post-misery artistic and spiritual growth is credible.

Similarly, del

Cerro brings an appealing vitality that adeptly captures

both the dewy optimism and the vulnerability of her character.

His spirit cannot be crushed by later off-stage elements (including an

unhappy affair), so her description near the end of the play of the joy

gained from post-misery artistic and spiritual growth is credible.Whiddon convincingly reveals inner torment as the obsessive-compulsive writer who believes his fame is a fraud. He is less reticent and awkward than some portrayals of Trigorin, but his sense of frustration and dissatisfaction is more palpable. This approach makes it more understandable that he might consider an ill-fated affair with Nina, despite knowing that it could prove crushing to the young woman.

The one flawed performance is Jacobson’s portrayal of the vain and self-centered mother. She makes the character immature, verging on childish, without having the convincing grandness of a diva actress. As a result, some of her scenes are discordant notes that puncture the overall mood of the play. For example, her efforts to persuade Trigorin not to delay leaving the countryside for the city turn into a broad comic seduction scene that is inconsistent with the mood of the piece and lacks authenticity given Chekhov’s conception of the two characters.

Overall, the

production moves smoothly despite occasional problems in tone.

One innovation - the characters occasionally sing from modern songs

while expressing their feelings carrying out their tasks (e.g.,

R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion”) - is a mild distraction in a play set in

the 1890’s Much more appealing is the use of some music by

Shostakovich for scene changes and underscoring.

Overall, the

production moves smoothly despite occasional problems in tone.

One innovation - the characters occasionally sing from modern songs

while expressing their feelings carrying out their tasks (e.g.,

R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion”) - is a mild distraction in a play set in

the 1890’s Much more appealing is the use of some music by

Shostakovich for scene changes and underscoring.Misha Kachman’s stark scenic design and realistic costumes work well in setting the mood and focusing attention on the ensemble cast. The cast is generally effective, although some of the minor characters seem downgraded slightly in this adaptation. One standout is J. Fred Shiffman’s spot-on Chekhovian character performance as Dorn, a compassionate yet resigned doctor who is a family friend and who later helps attend to the sickly Sorin.

While The Seagull on 16th Street will never displace the original, Theater J’s innovative production does provide an interesting perspective both on Chekhov’s work and the circumstances of Russian Jews. This approach to reinterpreting and rewriting a traditional text opens fresh doors for a company that has focused on new works. One wonders what classic adaptations with supplemental Jewish themes might follow. Based upon this production, I’ll be eagerly awaiting Artistic Director Ari Roth’s next creation.

The Seagull on 16th Street

Adapted by Ari Roth from the play by Anton Chekhov. Translation by Carol Rocamora. Directed by John Vreeke. Design: Misha Kachman (set and costumes) Dan Covey (lights) Matt Nielson (sound) Stan Barouh (photography) Kate Kilbane (stage manager). Cast: Veronica del Cerro, Cesar A. Guadamuz, Brian Hemmingsen, Nanna Ingvarsson, Naomi Jacobson, Tessa Klein, Mark Krawczyk, Stephen Patrick Martin, Jason McCool, J. Fred Shiffman, Alexander Strain, Jerry Whiddon.